Build a ChatGPT-Style GIS App in a Jupyter Notebook with Python

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are amazing. With computers, we can collect, analyze, and visualize geographic data in ways that were impossible just a few decades ago. We can explore cities, roads, parks, and real-world places directly on a map and use this information to make better decisions.

At the same time, GIS tools are often complex. They usually require learning many buttons, menus, and technical terms. Even simple tasks, like finding cafes or playgrounds in a city, can take time if you are not familiar with the software. This is where AI can help. A large language model (LLM) can understand natural language and turn simple sentences into actions. Instead of clicking through menus, you can just type what you want to see. AI becomes a friendly assistant that helps you use GIS systems faster and more easily.

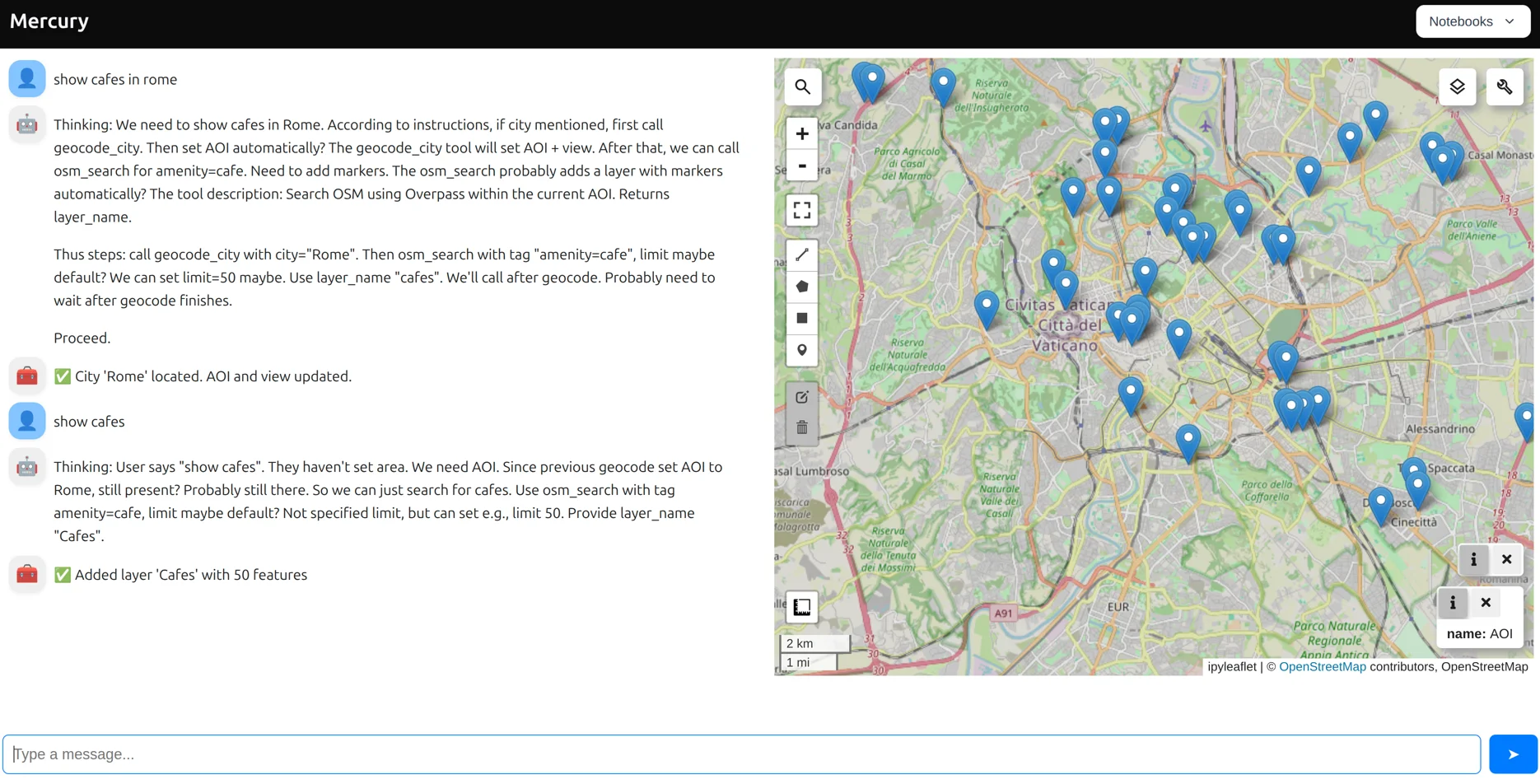

In this article, we will build a small but powerful example of this idea. We will create a ChatGPT-style GIS application inside a Jupyter Notebook - GeoGPT. You will type messages like “Show cafes in Rome” or “Find playgrounds in Warsaw”, and the map will update automatically.

We will use Python only. The map will be created with geemap. Geographic data will come from OpenStreetMap. The AI assistant will run locally using Ollama and GPT-OSS:20B. Finally, we will use Mercury to turn the notebook into a simple web application. By the end of this article, you will understand how chat, AI, and maps can work together, and how you can build your own natural-language GIS tools using Python and a notebook.

The GeoGPT notebook code is available in GitHub repository.

1. Setup local LLM model

To make our GIS app work with natural language, we need a local language model. Running the model locally is important because it keeps everything private and fast, and it does not require any API keys or external services.

In this tutorial, we use Ollama, which makes it very easy to run large language models on your own computer. It works well with Python and is a good choice for experiments and demos. Install Ollama by following the official installation guide. You can find it here: docs.ollama.com/quickstart

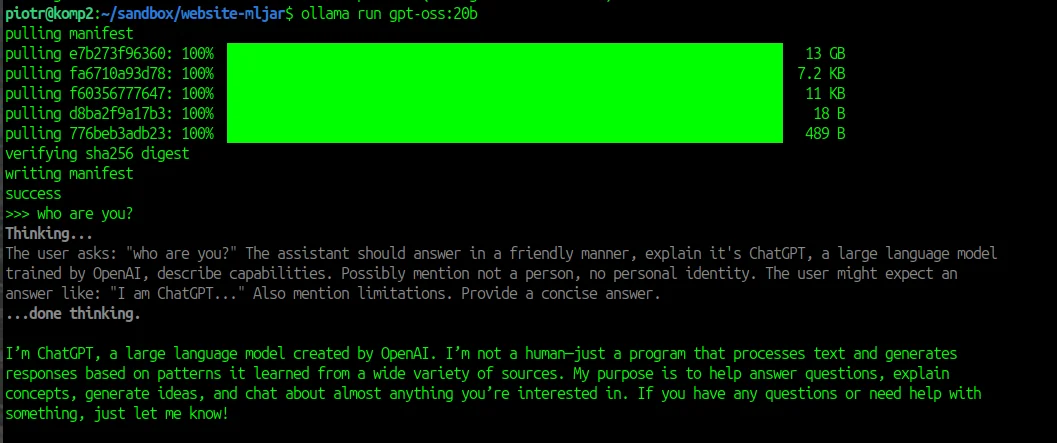

After installing Ollama, open a terminal window. We will download and start the model that we use in this article. The model is called GPT-OSS 20B from OpenAI. Run the following command:

ollama run gpt-oss:20b

The first time you run this command, Ollama will download the model. This can take some time, depending on your internet connection. Once the download is finished, the model will start and wait for input.

As long as Ollama is running, our Python code will be able to send requests to the model in the background.

2. Import packages and map creation

Now we need a few Python packages:

geemapto display an interactive map inside the notebook and later inside the Mercury app. Geemap is an open source and maintained by the geospatial community (geemap GitHub).- We will use the official Ollama Python library to send messages to our local model and receive responses with tool calls (Python Ollama GitHub).

- Finally, we will use

mercuryto turn the notebook into a web app and to display chat widgets, so users can talk to the application in a friendly way. Mercury is open source and available on GitHub. (Mercury GitHub).

You can install everything with pip. Run this command in your terminal:

pip install ollama geemap mercury

After the installation, we can create the map. In this tutorial we do not use Google Earth Engine, so we create the geemap map with ee_initialize=False. This is important because it lets us work with basemaps and OpenStreetMap data without any Earth Engine setup.

import json import requests import mercury as mr import geemap import ollama Map = geemap.Map(ee_initialize=False, center=[52.23, 21.01], zoom=12) Map.add_basemap("OpenStreetMap")

3. GIS tools for LLM

Before we connect the chat to the map, we need to define tools. Tools are regular Python functions that the AI is allowed to call. Instead of letting the language model directly change the map, we give it a small set of safe actions, such as moving the map, changing the basemap, searching OpenStreetMap, or adding markers. This approach is very important. It makes the application predictable, easier to debug, and much safer than letting the model generate arbitrary code.

Each tool does one simple thing. For example, one tool moves the map to a new location, another tool sets the current area of interest, and another tool queries OpenStreetMap using the Overpass API.

The AI only decides which tool to use and with what arguments. The actual work is always done by Python.

This is a common and recommended pattern when building AI-powered applications.

In our case, tools are also the bridge between natural language and GIS. When the user types “Show cafes in Rome”, the model does not search the map by itself. Instead, it calls a tool that first finds Rome on the map and then calls another tool that searches OpenStreetMap for cafes in that area. Thanks to this design, the AI feels smart, but the system stays simple and reliable.

In the next code cell, we will define these tools step by step. Once they are ready, we will tell the language model which tools exist and how it should use them to control the map.

def set_view(lat: float, lon: float, zoom: int = 12) -> str: """Set map center and zoom.""" Map.set_center(lon, lat, zoom) return f"✅ View set to lat={lat}, lon={lon}, zoom={zoom}" def set_basemap(name: str = "OpenStreetMap") -> str: """Set basemap. Examples: OpenStreetMap, Esri.WorldImagery, OpenTopoMap, CartoDB.DarkMatter.""" Map.add_basemap(name) return f"✅ Basemap set to {name}" def clear_layers() -> str: """Remove all added layers (keeps basemap).""" for layer in list(Map.layers)[1:]: Map.remove_layer(layer) return "✅ Cleared layers" def add_marker(lat: float, lon: float, label: str = "📍") -> str: """Add a marker with tooltip label.""" Map.add_marker(location=(lat, lon), tooltip=label) return f"✅ Marker added: {label} at ({lat}, {lon})" def set_aoi(bbox: list) -> str: """Set AOI bbox: [south, west, north, east] (Overpass order).""" if not (isinstance(bbox, list) and len(bbox) == 4): raise ValueError("bbox must be [south, west, north, east]") STATE["aoi_bbox"] = bbox south, west, north, east = bbox rect_geojson = { "type": "FeatureCollection", "features": [{ "type": "Feature", "properties": {"name": "AOI"}, "geometry": { "type": "Polygon", "coordinates": [[ [west, south], [east, south], [east, north], [west, north], [west, south] ]] } }] } Map.add_geojson(rect_geojson, layer_name="AOI") Map.set_center((west + east) / 2, (south + north) / 2, 12) return f"✅ AOI set to {bbox}" def osm_search(tag: str, limit: int = 200, layer_name: str | None = None) -> str: """ Search OSM using Overpass within the current AOI. tag must be 'key=value' e.g. amenity=cafe """ bbox = STATE.get("aoi_bbox") if not bbox: raise ValueError("AOI not set. Call set_aoi(bbox) first.") if "=" not in tag: raise ValueError("tag must be key=value (e.g. amenity=cafe)") k, v = [x.strip() for x in tag.split("=", 1)] south, west, north, east = bbox q = f""" [out:json][timeout:25]; ( node["{k}"="{v}"]({south},{west},{north},{east}); way["{k}"="{v}"]({south},{west},{north},{east}); ); out geom {int(limit)}; """ r = requests.post( "https://overpass-api.de/api/interpreter", data=q.encode("utf-8"), headers={"Content-Type": "text/plain"}, timeout=60, ) r.raise_for_status() gj = _overpass_to_geojson(r.json()) n = len(gj["features"]) lname = layer_name or f"OSM {tag} ({n})" Map.add_geojson(gj, layer_name=lname) return f"✅ Added layer '{lname}' with {n} features" def geocode_city(city: str) -> str: """Geocode a city name using OpenStreetMap Nominatim and set AOI + view.""" url = "https://nominatim.openstreetmap.org/search" params = { "q": city, "format": "json", "limit": 1, "addressdetails": 0, } headers = {"User-Agent": "Mercury-GeoChat-Demo"} r = requests.get(url, params=params, headers=headers, timeout=30) r.raise_for_status() data = r.json() if not data: raise ValueError(f"City not found: {city}") result = data[0] lat = float(result["lat"]) lon = float(result["lon"]) south, north, west, east = map(float, result["boundingbox"]) bbox = [south, west, north, east] # Set AOI and view set_aoi(bbox) set_view(lat, lon, zoom=12) return f"✅ City '{city}' located. AOI and view updated." # list of tools available for LLM TOOLS = [set_view, set_basemap, clear_layers, add_marker, set_aoi, osm_search, geocode_city]

The last code line is the most important. We create a variable called TOOLS. It is a list that contains all the tools the language model is allowed to use. Later, when we call the LLM, we pass this TOOLS list as an argument. Thanks to this, the model knows exactly which actions are available and which functions it can call to control the map.

4. System prompt

The system prompt tells the language model how it should behave in our application. It defines the role of the model and sets clear rules. Thanks to this, the model knows that it is a map assistant and that it should control the map by calling tools, not by writing long explanations.

The system prompt also helps the model understand how to translate simple user sentences into map actions. When the user asks for cafes, schools, or parks, the prompt guides the model to use the correct OpenStreetMap tags. When the user mentions a city, the model knows that it should first locate that city on the map.

Because the rules are clear and simple, the model behaves in a predictable way and the app feels easy to use, even for people with no GIS experience.

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """ You are a geospatial map assistant inside a web app. You can control the map ONLY by calling tools. Rules: - Prefer tool calls over explanations. - If the user asks to "show/find/search" something and AOI is missing, ask ONE short question: "What area should I search? Provide bbox [south, west, north, east]." - Use Overpass via osm_search(tag="key=value"). Supported tools: - set_view(lat, lon, zoom) - set_basemap(name) - clear_layers() - add_marker(lat, lon, label) - set_aoi(bbox) where bbox=[south, west, north, east] - osm_search(tag, limit=..., layer_name=...) - geocode_city(city) If the user mentions a city or place name, first call geocode_city. Tag cheatsheet: - schools -> amenity=school - cafes -> amenity=cafe - restaurants -> amenity=restaurant - parking -> amenity=parking - hospitals -> amenity=hospital - pharmacies -> amenity=pharmacy - playgrounds -> leisure=playground - parks -> leisure=park - museums -> tourism=museum - hotels -> tourism=hotel - supermarkets -> shop=supermarket After tool use, reply with ONE short sentence confirming what you displayed. """

We pass SYSTEM_PROMPT as the first message to the language model. This makes sure the model always knows its role and rules before it sees any user input. We also keep all messages in a list called messages. This list stores the whole conversation, so the LLM has context and can respond in a consistent way.

messages = [{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT}]

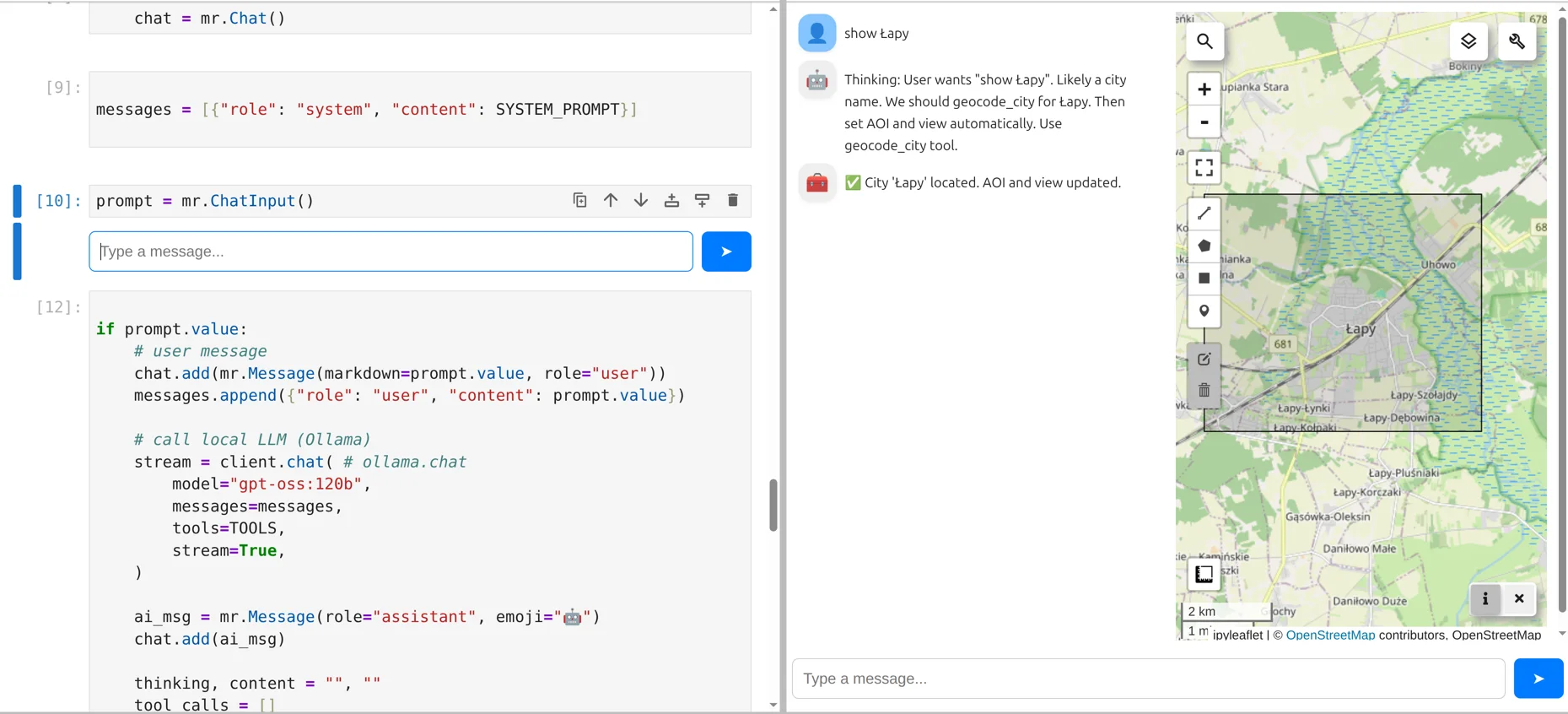

5. Create Chat UI

Let's create Chat UI with Mercury framework. We first create a two-column layout with Columns. This defines the structure of the page:

left, right = mr.Columns(2)

Next, we display the map in the right column. This must be done in its own cell so Mercury knows the map belongs on the right side of the layout:

with right: display(Map)

Then, in a separate cell, we create the Chat widget in the left column. We will display messages there:

with left: chat = mr.Chat()

Finally, the ChatInput field is created in its own cell as well. It will be displayed in the app bottom:

prompt = mr.ChatInput()

It is very important to place widgets in separate notebook cells when working with Mercury. Mercury builds the application layout based on cells, not on individual lines of code. Each cell defines where its widgets will appear in the final app. Because of this, widgets that belong to different parts of the interface must be created in different cells.

We can open live preview during Python notebook development:

6. Call LLM with prompt and tools

When the user enters a new message in the chat input, Mercury automatically re-executes all notebook cells below the updated widget.

This is one of the key features of Mercury and what makes building apps so easy.

You do not need to write any event handlers or callbacks. Updating a widget is enough to trigger the logic. The full code to handle a new prompt from user:

if prompt.value: # user message chat.add(mr.Message(markdown=prompt.value, role="user")) messages.append({"role": "user", "content": prompt.value}) # call local LLM (Ollama) stream = ollama.chat( model="gpt-oss:20b", messages=messages, tools=TOOLS, stream=True, ) ai_msg = mr.Message(role="assistant", emoji="🤖") chat.add(ai_msg) thinking, content = "", "" tool_calls = [] for chunk in stream: if getattr(chunk.message, "thinking", None): if thinking == "": ai_msg.append_markdown("Thinking: ") thinking += chunk.message.thinking ai_msg.append_markdown(chunk.message.thinking) if getattr(chunk.message, "content", None): if content == "": ai_msg.append_markdown("\n\nAnswer: ") content += chunk.message.content ai_msg.append_markdown(chunk.message.content) if getattr(chunk.message, "tool_calls", None): tool_calls.extend(chunk.message.tool_calls) messages.append({ "role": "assistant", "thinking": thinking, "content": content, "tool_calls": tool_calls, }) # execute tools for call in tool_calls: name = call.function.name args = call.function.arguments tool_msg = mr.Message(role="tool", emoji="🧰") chat.add(tool_msg) try: if name == "set_view": result = set_view(**args) elif name == "set_basemap": result = set_basemap(**args) elif name == "clear_layers": result = clear_layers() elif name == "add_marker": result = add_marker(**args) elif name == "set_aoi": result = set_aoi(**args) elif name == "osm_search": result = osm_search(**args) elif name == "geocode_city": result = geocode_city(**args) else: result = f"Unknown tool: {name}" tool_msg.append_markdown(result) except Exception as e: err = f"❌ Tool error in {name}: {e}" tool_msg.append_markdown(err) result = err # feed tool result back to the model messages.append({ "role": "tool", "tool_name": name, "content": result })

Let's analyze this code step-by-step. We start by checking if there is a new value in the chat input. If the user has typed something, prompt.value will contain the text. If it is empty, the code does nothing.

if prompt.value:

Next, we create a new chat message for the user. We add this message to the chat UI so it is visible, and we also store it in the messages list. This list is sent to the language model and keeps the full conversation history.

# user message chat.add(mr.Message(markdown=prompt.value, role="user")) messages.append({"role": "user", "content": prompt.value})

Now we call the local language model using Ollama. We pass three important things: the model name, the conversation history stored in messages, and the list of available tools. We enable streaming mode so the response is sent token by token instead of waiting for the full answer.

# call local LLM (Ollama) stream = ollama.chat( model="gpt-oss:20b", messages=messages, tools=TOOLS, stream=True, )

Before reading the response, we create an empty assistant message and add it to the chat. This message will be updated while the model is responding.

ai_msg = mr.Message(role="assistant", emoji="🤖") chat.add(ai_msg)

Now we process the streamed response. The model can send three different things:

- thinking text,

- normal response text,

- and tool calls.

We collect them separately. While the response is streaming, we update the assistant message in real time so the user can see what is happening. It gives a feeling that assistant is writing in real time.

thinking, content = "", "" tool_calls = [] for chunk in stream: if getattr(chunk.message, "thinking", None): if thinking == "": ai_msg.append_markdown("Thinking: ") thinking += chunk.message.thinking ai_msg.append_markdown(chunk.message.thinking) if getattr(chunk.message, "content", None): if content == "": ai_msg.append_markdown("\n\nAnswer: ") content += chunk.message.content ai_msg.append_markdown(chunk.message.content) if getattr(chunk.message, "tool_calls", None): tool_calls.extend(chunk.message.tool_calls)

After the response is finished, we save everything in the messages list. This includes the assistant text, the thinking part, and any tool calls. This way, the language model has full context when the next user message arrives.

messages.append({ "role": "assistant", "thinking": thinking, "content": content, "tool_calls": tool_calls, })

If the model requested any tool calls, we execute them next. Each tool call contains the function name and arguments selected by the model. We display each tool execution as a separate message in the chat, marked with a toolbox emoji.

# execute tools for call in tool_calls: name = call.function.name args = call.function.arguments tool_msg = mr.Message(role="tool", emoji="🧰") chat.add(tool_msg)

We then match the function name and call the correct Python function. This is done with a simple if-elif block. The map is updated here.

try: if name == "set_view": result = set_view(**args) elif name == "set_basemap": result = set_basemap(**args) elif name == "clear_layers": result = clear_layers() elif name == "add_marker": result = add_marker(**args) elif name == "set_aoi": result = set_aoi(**args) elif name == "osm_search": result = osm_search(**args) elif name == "geocode_city": result = geocode_city(**args) else: result = f"Unknown tool: {name}" tool_msg.append_markdown(result)

If something goes wrong, we catch the error and show it in the chat instead of crashing the app.

except Exception as e: err = f"❌ Tool error in {name}: {e}" tool_msg.append_markdown(err) result = err

Finally, we save the result of the tool execution. This is important because it allows the model to understand what actually happened and continue the conversation correctly.

messages.append({ "role": "tool", "tool_name": name, "content": result })

With this loop in place, the application feels interactive and natural. The user types a message, the AI decides what to do, Python executes the actions, and the map updates live.

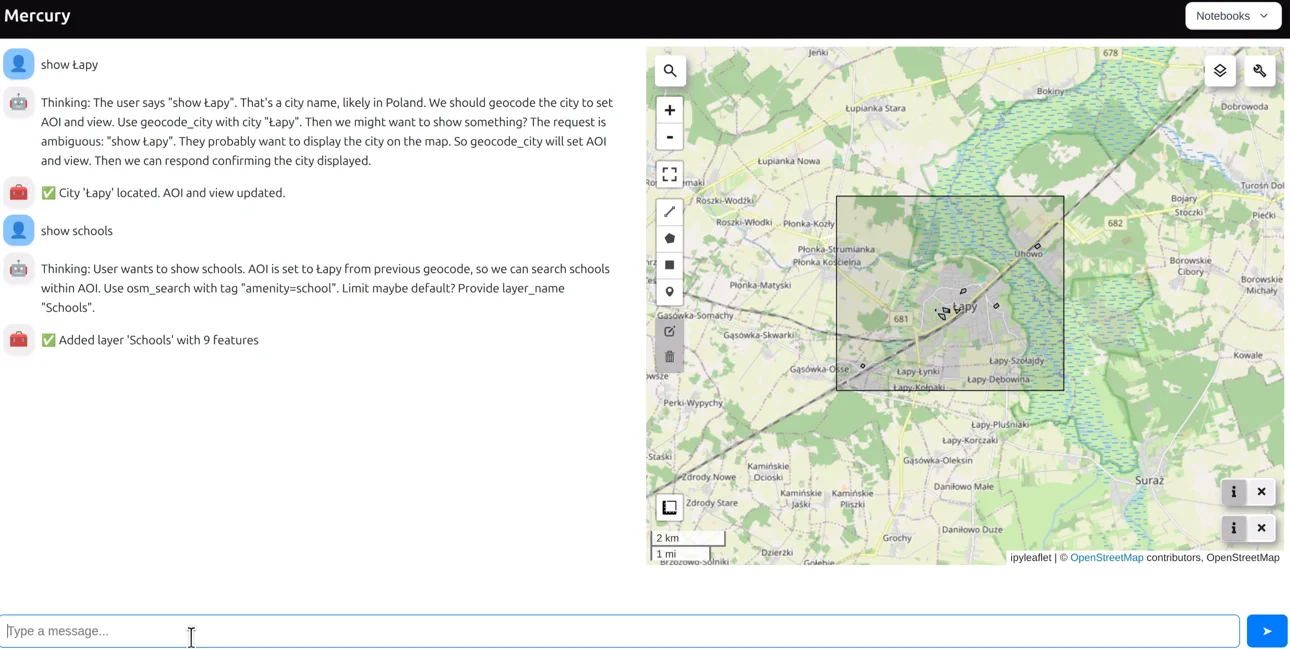

7. Running as standalone web app

We can run the notebook as standalone app with Mercury Server. Please start Mercury with command:

mercury

That's it. Mercury will detects all *.ipynb files in the current directory and serve them as web applications. The screenshot with app running:

Summary and conclusions

In this article, we built a simple but powerful GIS application using only a Jupyter Notebook and Python. We combined an interactive map, a chat interface, and a local language model to create a system that understands natural language and turns it into map actions.

We showed how Mercury can transform a notebook into a real web application without writing frontend code. We used geemap to display and control the map, OpenStreetMap as an open and reliable data source, and Ollama with a local LLM to handle user input in a natural way. By using tools, we kept the system safe, predictable, and easy to understand.

This approach lowers the entry barrier to GIS systems. Users do not need to know map interfaces, buttons, or query languages. They can simply describe what they want to see. At the same time, developers keep full control over what the AI is allowed to do.

The most important takeaway is that modern GIS applications do not have to be complex. With notebooks, open data, and local AI models, you can build friendly and powerful tools that are easy to share and extend. This pattern can be used not only for maps, but for many other data-driven applications as well.

About the Authors

Related Articles

- What is AI Data Analyst?

- Navy SEALs, Performance vs Trust, and AI

- New version of Mercury (3.0.0) - a framework for sharing discoveries

- Zbuduj lokalnego czata AI w Pythonie - Mercury + Bielik LLM krok po kroku

- Build chatbot to talk with your PostgreSQL database using Python and local LLM

- Private PyPI Server: How to Install Python Packages from a Custom Repository